Vitagraph 2 continued from page 1

lowered upper window, giving me a panoramic view of the

onrushing scenery (still with the help of the said seat,

alas).

From this

vantage point a rather unusual landmark near the Avenue M station

catches my attention: a smokestack. A very tall smokestack, with

serifed block letters running down it: VITAGRAPH Co. I ask my

parents about it and I'm told NBC has a studio there. Vitagraph =

NBC? (Better not to ask

about the discrepancy—you know how parents hate

that.)

I picked up bits and pieces about

Vitagraph over the years but I wouldn't learn all that utilitarian

structure represents until fifty years had passed, and it is a story

that is by turns ambitious and adventurous, wacky and inspired,

crowded with colorful characters and extraordinary achievements—in

short, the kind of thing that (in the words of the Jule Styne song)

"could only happen in Brooklyn."

What happened

actually began on the other side of the Brooklyn Bridge, where a film

company was founded by two young men from the other side of the Atlantic,

J. Stuart Blackton and Albert E. Smith, whose families emigrated from

England during their childhoods. Both had a flair for show biz and, with

the addition of fellow Brit Ronald Reader, performed in a novelty act in

which Blackton was billed as the "Komikal Kartoonist," Smith the "Komikal

Konjurer." The act did not prosper and Smith took a job as a bookbinder

while Blackton found employment as a cub reporter for the New York

Evening World. In this capacity (one story goes), he was sent to interview Thomas

Edison about his invention of a moving picture projector in 1896; in

the next year the two men reunited to form a motion picture company

they called American Vitagraph.

Its

first famous product, which has a claim to being the first real motion

picture made in America, was of a train called the Black Diamond Express,

augmented by the showmanship of the partners. As a photograph of the train

suddenly came to life, Smith provided billows of smoke while Blackton in

the wings manned dishpans, hammers and tin pie plates filled with dry

beans for sound effects. If indeed a first, it was but the first of many.

In Florence Turner, the "Vitagraph Girl," they had the first major film

star; a collie named Jean, the "Vitagraph Dog" ("no-one could help making

a fine story about her, and no actor could act badly in her support"), was

the pioneer in animal stardom. The first of the great screen comedians was

the "four-dimensional" funnyman John Bunny, whose death was mourned in

Europe as fervently as in America. The Battle Cry of Peace was

produced in 1915, with the outspoken approval of such luminaries as

Theodore Roosevelt, Admiral Dewey, Elihu Root and New York Mayor John

Purroy Mitchel, to prepare America for the war in Europe, demonstrated the

propaganda impact of the young medium. In the years between the Black

Diamond Express and The Battle Cry of Peace, Vitagraph became

the most creative and forward-thinking force in the

young industry, and it couldn't have happened without the studio it

built in Brooklyn.

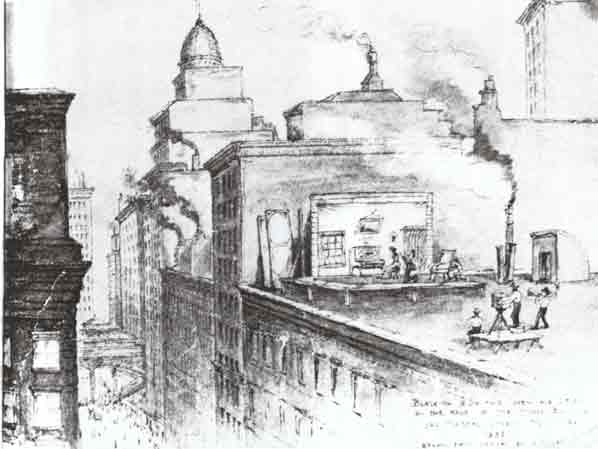

Vitagraph's “Open-air Studio” on the roof of Morse Building at 140 Nassau Street. (Sketch by Vitagraph co-founder J. Stuart Blackton, from Two Reels and a Crank, by Albert E. Smith.)

©2000 The Composing Stack Inc. All rights

reserved.

urbanography is a service mark of The Composing Stack

Inc.

Updated July 21,

2000.